A dark, true story about the collapse of American royalty.

GREY GARDENS: THE MUSICAL

America has always been captivated by scandal and even more so when it’s true. Grey Gardens, The Musical explores the tragic ruin of a mother-daughter family who go from glamor to squalor in the East Hamptons.

In the center of downtown riverside, large peaks of an old Queen Anne roof tower over an eclectic neighborhood of other heirloom homes. The slate blue Lightner House’s front lawn is sectioned off with cocktail tables, filled with guests and quiet conversation. The windows on the old house are tall, softly lit and are graced by the occasional, drifting shadow like ghosts wanting their presence known.

It feels like a party, complete with perusing Champagne servers and filler music at a polite volume, transporting you to the garden parties of legend in the East Hamptons. However, the house’s condition is ever present: exposure to the elements has muted the colors, the paint has peeled, and a faded relic of the 1890s stands mistreated. The mood is set for the fall American royalty, only one degree removed from the Jackie and John Kennedy, Edie and Edith Bouvier Beale.

The lawn music turns into song, an old tune “The girl who has everything”, sung in a wavering duet from the shadows of the windows. Faces peer out from lacy, dirty curtains donned with binoculars and headscarves. The audience is transformed from mere party guests to the prying, gossip columnists of the 1970’s, wondering whatever happened to the reclusive Kennedy-related women. They were scandal. They were sharing the papers with the notorious Elizabeth Taylor. We couldn’t simply leave them, and their old house, be.

Ushered across the large, disheveled porch, there are trash and cat food tins. Tins. And tins. And Tins. The creaking floorboards shift with uncertainty at the volume of fifty people making their way through the beautiful flanked rose window parlor door. The audience takes a seat in 1941 at the social event of the year: Edie Beale’s engagement party.

ACT ONE

The parlor is luscious, refined and restored to its proper glory, in stark contrast from the trash filled porch. The intimate floor seating makes the entire house its theater, which is charming but cramped, due to the amount of people clamoring to be inside.

Instantly, I am blown away by the voices of the actresses. Edith, played by Karen Macarah, fills the space with her powerful voice, showcasing a weird, dramatic, array of songs. She does not shrink away from the challenge of playing the exaggerated, sensational mother, with perhaps a greater love for the stage than even her own daughter’s happiness.

Flanked by the hopeful, love struck Edie, who’s voice is equally as commanding and played by Sallie Griffin; both women bicker bitterly, standing diametrically opposed in want and need, but loving one another, at least in 1941. Griffin uses her voice in vigorous ways, to both challenge and plead with her mother counterpart, seemingly to beg in the only language Edith understands: grandiose gestures.

Edie, on the verge of escaping her mother’s fantasy and gilded cage that is the estate of Grey Gardens, only has one request: “Please don’t sing.” The melodramatic Edith has scared away suitor after suitor and made the whole extended family both weary and ostracized. Now, engaged to the ruggedly handsome Joe P Kennedy Jr, her life can finally change. But change doesn’t seem to be in the cards as it all falls apart before us. The engagement dissolves in a myriad of accusations against Edie’s character, fueled by her mother in jealousy and hurt.

Both fragile and desperate, Edie Beale watches as her engagement collapses. The visceral hurt are sung in a coarse and raw melody by Sallie Griffith, who truly believes her Father’s word will save the image of her moral character. When he gets home, it will be okay. It will be okay if Joe just listens. Her achievement in this song is the gravity in her sorrow. Edie needs her father to save her, to save the future of her marriage and to save any future at all outside Grey Gardens. He skips the party. He’s divorcing Edith publicly. He has his fingers crossed for his daughter. He sends his love. Joe leaves and Edie’s future leaves with him.

In the final song of Act One, “Will You?”, Edith has no time to cancel the party. Instead, tearfully and full of false bravado, she sings a melody dedicated to young love, with resounding, tragic sadness. Wherever Macarah pulled inspiration from was place of deep, deep pain. As a mother protecting her daughter paired with regret and shame about her actions, she defers questions about the engagement. She smiles with glistening, red eyes and thanks everyone for coming as Edie bolts out of Grey Gardens with a forceful slam of the door. 1941 ends with both a whimper and a bang.

ACT TWO

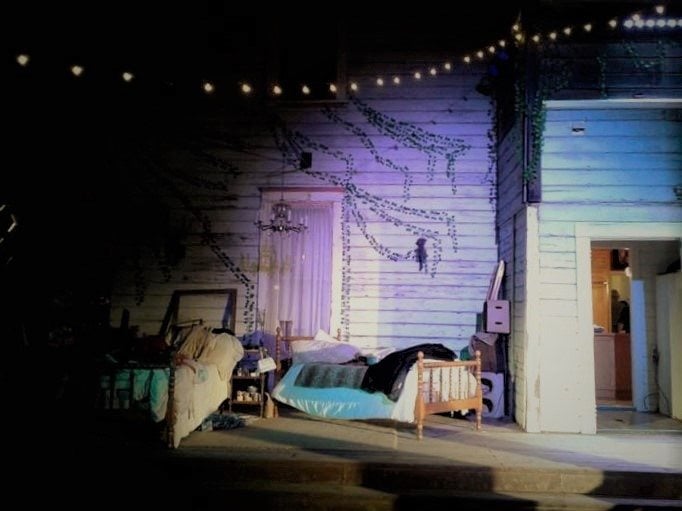

After intermission, we’re ushered through the dining room and into the backyard to enjoy a cool, June evening. Blankets are graciously distributed and proscenium seating provided. The back deck is nearly as long as the house itself and in terrible condition. The rear of the house is covered in holey drapes and unkempt ivy, a stark contrast to the refined parlor. The women are in disarray, as neglected as the house, and now it’s 1973.

The spiral into madness begins almost immediately. There’s a shift in the character portrayal, since thirty-two years have passed. Karen Macarah now plays the aged daughter, Edie. A new actress, Diane David, plays the older, ailing Edith. All the charm and sophistication of Grey Gardens has evaporated, as has the money. The women are shrill and reclusive now. The health department wants to condemn the estate. Their famous cousin, Jackie Kennedy, is avoiding all mention of it in the papers.

They rely on unreliable individuals, hoard animals and maintain delusions about what life could have, and should have, been. All they have is one another and it’s unfair.

A few songs stand out, one for its sheer bizarreness, another for its curious euphemism, and the other again for the emotional commitment of Macarah. The set change was great. Outside, are two beds, bringing the elements into the decapitated bedroom of the manor. With the peeling house as the backdrop, the sense of pure destitution was ever present.

“Entering Grey Gardens” was performed by the entire company and is whole-heartedly, entirely, completely weird. The ensemble proceeds to slink around the backyard and porch, meowing and grooming, while the song is a love ballad from…cats to the estate. It was delightfully crazy: “It’s like a twenty-eight room litterbox/ One-hundred-fifty windowsills/ To catch a wink or two/ And that’s Grey Gardens from a cat’s eye view.”

It was done very quickly into the second act and I was not prepared. I don’t think anyone was. But for as weird as it was, it was a great use of the outside space.

Secondly, “Jerry Likes My Corn” was wild and done super subtly, where by the end, my eyes were squinted in narrow, accusing slits. Edith has a high school boy, Jerry, help around the house. The mother’s life in old age consists of bed confinement, a record player and a hot plate. In this hot plate, she makes corn. Jerry eats said corn and keeps coming back for more.

Sung affectionately by David in bed, she disparages between how helpful and willing Jerry is, in direct contrast to useless Edie. Edith adores him. She offers him alcoholic drinks. She butters his corn for him.

Finally, Edie decides to run away and live her life. Only fifty-two, it’s still possible and again she fondly remembers her youth in New York. However, “Another Winter in a Summer Town,” is a sad song of ultimate surrender. Cramming her things into a suit case, Edie is going to do it, she’s going to finally leave and will never be drawn back. Running down the stairs, coat flaring in the wind, she pauses and leans on the porch banister and stares out into the world. Where has her courage gone? Edith cries out for her. Edith can’t survive without her.

There is a great part of this scene where both mother and daughter are highlighted in spot light. As Edie mournfully sings, terrified of surviving another winter in the Hamptons, her younger self (Griffins) is seen packing her bags feverishly in 1941, equally pausing to fear the future. Both actresses sing and while the younger version runs away, the older woman drops her suitcase, unable to make an exit. Edith shrilly calls out her demands. She needs food. She needs companionship. The cats need to be fed. It’s cold.

Regretfully, she climbs the porch steps again, consumed by the house. Edie sits by her mother and listens to a reprise of “The girl who has everything”. Finally, both winter and darkness settle in.

CONCLUSIONS

Grey Gardens the Musical originally hit Broadway in 2006, with the original documentary playing 1975. Today, with this production, the most ambitious thing about this is the use of a historical house as a set. The house itself is owned by the producer of the show and director of Riverside Rep theater, David St. Pierre. Inside, while very livable and fully functioning, has been converted to a theater in the technical sense with stage lights and sound systems.

Using the house, which seemed almost tailor made to this riches to rags story, was a brilliant plan. I don’t know if I would have been so engaged in the story if the setting hadn’t been so unique and nay, perfect. Also perfect was the casting. Every actor and actress was fully invested in their characters. The grandfather Major Bouvier, was fantastic in his terrible, but appropriate, 1940’s song, “Marry Well.” Mark Ziemann, playing George Gould, had fantastic witty banter and played the perfect enabler to a younger, more theatrical centered Edith.

Also, Desmond Clark portraying Brooks, the butler/gardener/everyday man, worked as both an actor, a crowd wrangler and a constant moving piece of the play. Especially before and during intermission, he helped audience members navigate the house. I feel here, was the strongest hint of immersion, because he was ever present. I wish he was utilized even more, rather than deferring some tasks to stage hands or REP staff, to keep the illusion up.

Talking at the audience and sitting in a sight specific theater isn’t immersion. Certainly, there were elements of it – the mixer beforehand or idling in the house during intermission. However, there is zero audience participation. Any interaction truly feels incidental because of the intimacy of using a house as a stage, rather than any purposeful planning. In short, if Grey Gardens was done in a traditional theater, the level of interaction wouldn’t change. And more disappointingly, I feel with this specific production, it could have been realized but maybe the older audience wasn’t ready for that level of commitment.

This I can forgive, but must be said: logistically, it was a bit of a mess. It was the curse of plenty. There were nearly fifty people as a roaming audience and that was too many. Easily, twenty-five would have been a good number to move comfortably. When first entering the parlor, the production came to a complete halt as REP staff scrambled to delegate seating or even to find more seats. Then the show would resume. Again, in the beginning of the second act, there was this interruption of staff. The simple volume of attendees is great for theater as a whole, but was a clear hindrance in this rare house setting.

Three fantastic songs stood out from act one. “The Five-Fifteen” was a fun, energetic up-beat song performed by nearly the whole company and an excellent beginning to set the mood. It showed off a variety of talents either in scale of notes, choreography or actor-to-actor interaction, all which were engaging and well executed. In contrast, the other two songs, “Daddy’s girl” and “Will You?”, lacked any joy or positivity, and were marvelously sung by both women.

In act two, the production becomes wild and everyone (cast included) embraces the wild, downward spiral that is Grey Gardens. The somber, wrenching end of “Another Winter in a Summer Town,” leaves this resounding feeling of dreams unrealized, potential unfulfilled and again, another year gone. It’s an odd feeling to conclude on but completely appropriate as Grey Gardens is a tragedy, sung by tragic characters.

Overall, this production was ambitious and professionally executed by proficient people. They tried something challenging in a visionary setting and it was an obvious labor of love. The cast is talented. The house was its own character. I had caught up to St. Pierre to ask what had come first: the house or Grey Gardens, because this pairing appeared so natural. He smiled and said during a REP board meeting it just dawned on them, they needed to do it; like it was destiny.

Will such a perfect merger of story and set ever happen again? I look forward to whatever the Riverside Repertory Theater puts out in the future and 2017 isn’t over yet.

In the Inland Empire? Keep an eye on the Riverside Repertory Theater and their 2017 seasons via their website.